Interview with Stan Pranin

We thought it appropriate that our first interview in AT be with Stan Pranin, editor of the world’s foremost Aikido periodical Aiki News. After beginning Aiki News in California, Stan moved to Japan, where he now studies with Saito Sensei.(Edited 2018 – Originally published in Aikido Today, April 1987)

AT: You are the editor of the magazine Aiki News, a focal point of the worldwide Aikido community. From your vantage point, does it seem that the community is splintering or that it is somehow coming together?

AT: You are the editor of the magazine Aiki News, a focal point of the worldwide Aikido community. From your vantage point, does it seem that the community is splintering or that it is somehow coming together?

SP: Aikido is definitely splintering into separate groups, but there are some groundsfor hope that people will be coming together. The splintering tendencies have been around for a long time, even in the pre-war period. For example, O’Sensei’s nephew, a man named Noriaki Inoue, parted ways with O’Sensei and went on to found an art that he calls Shin’ei Tai Do. Although Inoue Sensei insists that its essence is different, Shin’ei Tai Do’s techniques are virtually indistinguishable from Aikido’s. Another important split involved Gozo Shioda Sensei. Here there was no formal separation from the Aikikai, no dispute or rupture. In the early fifties, Shioda Sensei was able to receive some fairly strong financial backing from bankers and other higher-ups. He was also able to be involved in the instruction of the police quite early. At the same time, the Aikikai was in a moribund state. There were very few people practicing, and O’Sensei was in Iwama. So, what happened, as far as I have been able to determine, was that Shioda Sensei started up Aikido Yoshinkan and was successful earlier than the Aikikai. There was talk of the Yoshinkan’s being absorbed back into the Aikikai, but that never happened.

During the War, a split started involving Kenji Tomiki, who was heavily influenced by Jigorō Kano of Judo. Tomiki wanted Aikido to develop along the lines of Judo, and he endeavored to create a competitive system. His base for spreading this type of Aikido was Waseda University. Being a professor at the University, he had high standing in certain circles. In Britain, the Tomiki-style Aikido people are involved in police instruction to a great extent. And there are some dojos practicing this style in the U. S.

The next really major split that occurs to me is that of Koichi Tohei, who formally separated from the Aikikai in 1974. For several years preceding that, the Hombu dojo was divided into two camps. When I studied there in the summer of 1969, many of the people who trained with Tohei Sensei came to the dojo just for his classes. Conversely, many people who trained with the other Aikikai teachers would not appear in Tohei Sensei’s classes. So, there were already lines of demarcation prior to the formal split. Tohei Sensei had founded his Ki No Kenkyukai while still the chief instructor of Hombu Dojo. Following the separation and his departure from Hombu Dojo, he spent full time at the Ki No Kenkyukai and named the Aikido taught their Shin Shin Toitsu Aikido, which emphasizes his interpretation of the concept of Ki. The organization is world-wide and includes hundreds of dojos.

During the War, a split started involving Kenji Tomiki, who was heavily influenced by Jigorō Kano of Judo. Tomiki wanted Aikido to develop along the lines of Judo, and he endeavored to create a competitive system. His base for spreading this type of Aikido was Waseda University. Being a professor at the University, he had high standing in certain circles. In Britain, the Tomiki-style Aikido people are involved in police instruction to a great extent. And there are some dojos practicing this style in the U. S.

The next really major split that occurs to me is that of Koichi Tohei, who formally separated from the Aikikai in 1974. For several years preceding that, the Hombu dojo was divided into two camps. When I studied there in the summer of 1969, many of the people who trained with Tohei Sensei came to the dojo just for his classes. Conversely, many people who trained with the other Aikikai teachers would not appear in Tohei Sensei’s classes. So, there were already lines of demarcation prior to the formal split. Tohei Sensei had founded his Ki No Kenkyukai while still the chief instructor of Hombu Dojo. Following the separation and his departure from Hombu Dojo, he spent full time at the Ki No Kenkyukai and named the Aikido taught their Shin Shin Toitsu Aikido, which emphasizes his interpretation of the concept of Ki. The organization is world-wide and includes hundreds of dojos.

There have been other splits which are not quite as well-known. In the States, the clearest example probably would be Saotome Sensei, who has connections with the Aikikai on a personal but not an organizational level. Unable to come to terms with Japanese teachers residing in the U.S., Saotome created a separate organization known as Aikido Schools of Ueshiba. This organization has quite a large following, and many dojos are associated with it.

There have been other splits which are not quite as well-known. In the States, the clearest example probably would be Saotome Sensei, who has connections with the Aikikai on a personal but not an organizational level. Unable to come to terms with Japanese teachers residing in the U.S., Saotome created a separate organization known as Aikido Schools of Ueshiba. This organization has quite a large following, and many dojos are associated with it.

In France, there are a great many Aikido practitioners — perhaps even more than in Japan. One French organization has dojos in England, Canada, and most of the European countries. It is so strong that it could become independent of Hombu dojo and go right along with business as usual. In fact, this sort of separation has sometimes been hinted at. It’s certainly a possibility that a separation could occur there.

What about the other side of the picture — Aikido’s coming together? I think that one of the most significant factors holding out hope for those who want to see a more united movement is that there is so much travel going on. A Japanese teacher might go abroad to instruct, and he might teach a seminar open to the general public. Members of three or four different organizations which normally don’t have very much contact might train together on the mat. It sometimes happens that the individuals participating will enjoy the teacher’s presentation, establish an independent relationship with him, and invite him to visit their dojos. This has happened many times. So, travel by well-known teachers to various parts of the world has had a sort of a cross-fertilization effect, which is very healthy.

Another factor, of course, is the number of foreigners studying Aikido in Japan. At any given time, there are several hundred people from all over the world studying in various Japanese dojos. This, too, has a very positive effect.

Now, as to the part of your question about Aiki News — we have been in existence for 14 years now, and we have published about 2300 pages. We have readers in about 25 countries. People from all over the world can read — in Japanese or English — about the top teachers of all major styles of Aikido, about the predecessor art to Aikido (Daito Ryu), about the earliest phases of Aikido, and about what O’Sensei did in the last years of his life.

This type of information, I think, tends to develop a consciousness of a common heritage among Aikido practitioners — to develop open-minded-ness and an acceptance of various approaches to the art. If information about our shared history were not available, people in Aikido would only see the technical and organizational differences that separate them.

This type of information, I think, tends to develop a consciousness of a common heritage among Aikido practitioners — to develop open-minded-ness and an acceptance of various approaches to the art. If information about our shared history were not available, people in Aikido would only see the technical and organizational differences that separate them.

Also, within Aiki News, we’re going to be doing some things which will make it easier for readers to communicate with each other. People who want to travel or who are, say, looking for a particular document will be able to write in and have their questions answered. For example, in the next issue of Aiki News, we’re publishing a letter from Lichtenstein, a very small country physically surrounded by Switzerland. The Lichtenstein Aikikai is looking for Japanese teachers, or at least least black belts, to spend short periods of time in their country in exchange for room and board.

Whereas it might seem impossible for a group like that to express its wishes internationally, Aiki News makes this sort of thing feasible. So, I would say that, although the Aikido community does seem to be splintering, there are still some hopeful tendencies. I like to think that Aiki News has played a fairly significant part in developing those tendencies, as I have explained.

AT: Aiki News recently held the second Friendship Demonstration, in which leading Aikidoists from various styles demonstrated the art. How have the Friendship Demonstrations helped to unify the Aikido community? Are there plans for a third?

SP: The Friendship Demonstration series, which began in 1985, allows many different teachers to present their viewpoints of Aikido. While on the stage performing, they talk about what they regard as the essence of the art and also demonstrate their techniques. The demonstrations are, of course, made into videos which have quite a wide distribution. Literally thousands of people have seen first-hand, in a way very close to being physically present.

I think that the demonstrations tend to breed a tolerance for, if not an acceptance of, different viewpoints. In many cases, they stimulate people to study with particular individuals whom they find suit their approach. Sometimes people come to Japan to study Aikido with a specific teacher just because they’ve seen that teacher in a video. In this sense, the demonstrations can help to unify Aikido.

AT: What difficulties do you face in publishing a magazine for Aikidoists with different styles, different affiliations, and different ideas about the nature of the art? Have you had to do any political juggling?

SP: Well, [laugh] that’s a tough one to answer. Have I had to do any political juggling? Yes, on a daily basis. It’s been tough — very tough. Just writing history is extremely political — at least when the organizations still exist or some of the participants in the historical events are still around. If I write memoirs in my old age, there will be all sorts of interesting tidbits in them about behind-the-scenes maneuvering that we’ve had to do. Putting out Aiki News has been very tricky. Now that we have been around for such a long time and our readership is growing, I feel a little more stable. But there have been times when I feared for the publication’s existence.

I’m not afraid to print something that’s critical of O’Sensei, provided that the author has good reasons for believing it and his viewpoint is significant historically. Who wants to read a biography of a famous personage which only says positive things?

The author would quickly be dismissed as superficial and one-sided. Since O’Sensei’s death is not so far removed historically, many people are sensitive to the criticisms of him which we have occasionally published. But, if you take the favorable viewpoints of O’Sensei that we have published and line them up alongside the criticisms (which you can count on the fingers of one hand), you see things in perspective.

AT: Do you have any amusing stories about the beginnings of Aiki News that you can share with us on the occasion of our starting Aikido Today?

SP: Well, for the first issues of Aiki News, we had to justify the text (that is, make the right margins even) by typing articles and then counting the characters in each line. Unless a line happened to have exactly the right number of characters in it, we had to move a little space adjustment on our IBM S electric typewriter and add half spaces here and there. It was extremely tedious. Typing one article would take hours and hours.

A couple of years after the beginning of publication, when I moved to Japan, I bought a used Japanese typewriter — an incredible monstrosity. You moved a tray with about 2000 characters in it, then moved a lever over the appropriate character, and then punched down. The type was drawn up and made an impression on the page. Well, for a foreigner to try to learn the order of the characters on the tray… it took me hours and hours and hours. But I actually typed all the Japanese text of issue #30 myself. That was the only time I did it. [laugh] It was an exhausting and time consuming experience, but one that I’ll never forget.

Then there were the problems of getting students to fold and staple Aiki News. Once, when I made the mistake of saying that an issue was about to come out, the number of participants in my class was much smaller than usual. Nobody wanted to be cornered into doing folding and stapling work afterwards. So, after that, I would always bring out the stacks of printed pages and envelopes unannounced.

Then there were the problems of getting students to fold and staple Aiki News. Once, when I made the mistake of saying that an issue was about to come out, the number of participants in my class was much smaller than usual. Nobody wanted to be cornered into doing folding and stapling work afterwards. So, after that, I would always bring out the stacks of printed pages and envelopes unannounced.

An awful lot of volunteer labor went into the publication in those early days. One of my good friends wrote a song called the Aiki News Blues in which she described the trials and tribulations of publishing the thing and trying to get it in the mail.

I hope I haven’t given the impression that Aiki News has been a one-man operation. There have been periods when it has been essentially a one-man operation, but, for at least the last several years, it has been a [laugh] two-man operation — and more recently a three-person operation. I have to give great credit to my managing editor Ikuko Kimura; any improvements in the layout of the publication are almost 100% due to her efforts and imagination. More recently, we’ve had another employee, Fumiko Ito, who has been a welcome addition to our staff.

Well, maybe that’s enough about Aiki News. There are many more stories, but [laugh] some of them I wouldn’t want published.

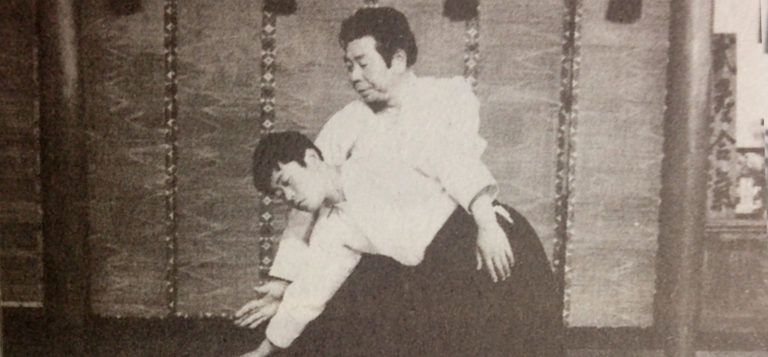

AT: The technical section of Aiki News seems always to feature Morihiro Saito Sensei. Is this because you regard his style as a standard for all students of Aikido to follow?

SP: Saito Sensei does appear regularly in the technical section of Aiki News, but I do not mean to imply that his is the standard form of Aikido or the one that everyone should practice. Let me explain something about Aiki News. Some people seem to think of it as if it were an officially authorized publication whose purpose is to represent some Aikido organization. But, until very recently (and even sometimes now), it’s Stanley Pranin who pays for the publication of Aiki News. Of course, people who buy subscriptions and tapes help us out. But I’ve sunk so much of my own money into the publication of Aiki News that I don’t even want to know the amount. It would horrify me.

I feel, then, that I can allow myself the luxury of indulging myself in certain aspects of the publication. This shows up in our coverage of Saito Sensei and in the fact that he is a permanent fixture of the Friendship Demonstration. Saito Sensei has been my teacher for 10 years now. Although I have not formally been his uchi deshi, I have traveled abroad with him — to Europe for the most part — and we have spent anywhere from two weeks to a month together every day.

He is a person for whom I have great respect, and I believe very much in what he is doing. Consequently, I have sought to give good coverage in Aiki News to him, his technique, and his viewpoint of the art.

AT: We’ll end by asking a question that we hope to ask of everyone we interview: What do you regard as the essence of Aikido?

SP: I offered my definition of Aikido once in an editorial [Aiki News #59 — eds.] and I’ll repeat it here:

Aikido is a modern Japanese martial art developed by Morihei Ueshiba including mainly joint-lock techniques applied in self-defense with the intent of not injuring the adversary. This definition says something about where Aikido began, who started it, what kind of techniques are involved, and what the philosophy is behind the art.

AT: Thank you for the interview.