Interview with Morihiro Saito

Interview with Morihiro Saito

Originally published in Aiki News #88

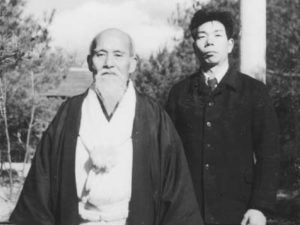

Aiki Shrine guardian, Morihiro Saito, began training with Morihei Ueshiba at Iwama in 1946 at the age of 18. During his years as uchideshi, Saito Sensei learned jo and sword techniques directly from the founder. In this interview, conducted in March 1991, Saito Sensei talks about his experiences with O-Sensei, his early days at the Aikikai, his own dojo and his training methods.

Editor: Not many of our readers know that you taught as a shihan at the Aikikai in Tokyo for a long time. Would you tell us some of your memories of that period?

Morihiro Saito: I taught at the Aikikai once a week except for a period in 1961 when Ueshiba Sensei went to Hawaii with Nobuyoshi Tamura. We were short-handed in Tokyo, so I taught twice a week during their absence. Apart from that I mainly taught on Sundays.

During your Sunday classes you taught ken and jo after taijutsu practice, didn’t you?

Yes, with O-Sensei’s approval, I taught weapons techniques for the last 15 minutes of practice.

Was the present sanjuichi-jo (31-movement jo kata) finalized before O-Sensei’s death?

Yes, by the time I learned it the kata was already complete, but when Koichi Tohei Sensei [presently head of Shinshin Toitsu Aikido] came to practice in Iwama it had not yet been perfected. What he learned was different from what I learned, probably because O-Sensei’s way of instructing was not yet fully developed. When I learned under O-Sensei his teachings included all of the weapons techniques including the kumitachi. At one stage, there was no one left in Iwama except me, so I trained with O-Sensei by myself. His teaching gradually became more elaborate.

Did you teach the kumijo in Tokyo?

Not really, except to a few people in odd places such as on the rooftops of buildings. I used to teach the jo as a 27 or 28-movement form, but ended up with the 31-movement form as I found this was easier for students to understand. Just as my aikido has come to be called “Iwama-style,” the “sanjuichi-jo” name that I gave to this kata has stuck.

What should aikidoka from overseas do if they want to come to Iwama to practice?

They should get a letter of introduction from someone. Then they need to stay for at least 10 days. If they are not from a dojo directly affiliated with us, it would be difficult to learn anything during a one-week visit and such people may leave our dojo without understanding anything and speak ill of us. For my own students one week is enough but for a person from a different school a minimum stay of 10 days is necessary. Anything less could be counterproductive.

Take the case of the Japanese university students who come to Iwama to train during their summer vacation. Their hips are not trained properly at all, so I have to correct their hip movements every morning during weapons training. They finally begin to use their hips correctly around a week before they leave, just when I am about to give up on them. It takes them three weeks to grasp this basic point. Even in ten days it is not easy, but those who come to Iwama from abroad are fine people and train hard.

How do the uchideshis in Iwama spend their time?

The dojo grounds are quite extensive and cannot all be cleaned at once. When they get up in the morning they first clean their own rooms, then the practice area, and then they sweep carefully in front of the shrine. The grass has to be mowed in the summer, so they sometimes help me with the power mower. It would be impossible for me to keep the place clean all by myself so the students naturally help with the cleaning. As a result of their efforts the shrine is always kept clean. Without this work their lives would be more comfortable, but they are all patient, fine people and there have been no objections.

Do you still teach weapons techniques every morning?

Yes, I do. Students also do free practice. There is plenty of space in the new dojo so they are free to practice kata. I am pleased that overseas students enjoy practicing in the new dojo, but we still regard the original dojo as the main one, and train there for preference whenever possible.

Training camps (gasshuku) have been held at the Iwama dojo for many years haven’t they?

We have had them ever since O-Sensei’s days. He was always pleased when he heard that a training camp was to be held. To prepare for these camps we used to make our own futon (bedding). Each night after practice we would sew futon covers and stuff them with cotton.

I am surprised to hear that you had to do such things! How many schools participate in your training camps now?

We have Hirosaki University from Aomori Prefecture and Tohoku Women’s University, both from Northern Japan, Tokushima University from Shikoku, and others such as Osaka Prefectural University, Iwate University, Tohoku University, Tohoku Gakuin University, Miyagi Prefectural University of Education, Kanagawa University and Nihon University. Since they all come at the same time, in March, it is hard to accommodate them all.

Are these combined training camps?

Yes, when the clubs are under the same shihan. For example, when Aichi Medical University holds a training camp, Kanagawa University will also participate.

You first went abroad to instruct in 1974 and since then you have traveled almost every year, perhaps more than any other shihan?

There are many invitations I can’t refuse, although I only visit dojos operated by my own students. But these days I try to stay here as much as possible because of the number of students here and for the sake of those who visit Iwama to study.

Historically, I think aikido developed from situations where a samurai could not use his sword. Some critics say aikido won’t work against modern fighting systems like karate. What do you think?

Aikido includes tanto dori (short sword taking), tachi dori (sword taking), and jo dori (jo-taking). During such techniques, if you allow the blade of a weapon even to touch your body you could be killed, whereas a punch or kick will not kill you unless it strikes a vital point. A sword need only make slight contact to seriously injure or kill; yet we practice how to defend against the sword with our bare hands. If we always bear this in mind it is valuable training.

Do you think that aikido without atemi can be effective against a strong attack?

Aikido includes atemi, although of course training is not the same as reality so we do not apply atemi fully in the dojo. In taijutsu, atemi is a vital element that we emphasize in our dojo.

It has been my experience that atemi is not taught in many aikido dojos today, but in his films we see that O-Sensei often used atemi.

Aikido is now being taught in many different ways, and it is good to learn from different teachers. We should not forbid students to go to other teachers. There are some shihan who make a fuss about this but I think they are mistaken.

In aikido atemi is used against attacks with a weapon, so do you think that it is desirable for aikidoka to learn how to cope with karate kicks now that karate-like attacks are often used?

Yes, I think they should. It’s not something to be avoided. There are many basic techniques, which can enable us to cope with karate, such as tsuki and yokomenuchi.

A group established by some of my students does a form of defense against karate attacks, which is quite interesting. A man with a 4thdan in both aikido and judo dodges the karate attacks and steps in to throw or pin his attacker in a splendid performance of aikido techniques. I would also recommend plenty of practice of such techniques as yokomenuchi and tachi dori.

You place strong emphasis on weapons and base your teaching on the principles of the sword. What do you think of the present situation elsewhere in aikido?

I don’t know any aikido other than O-Sensei’s. I was taught by O-Sensei from the age of 18 to 41 and served him in the same way as a live-in student, so I don’t know any other teacher. Many shihan create new techniques and I think this is a wonderful thing, but after analyzing these techniques I am still convinced no one can surpass O-Sensei. I think it is best to follow the forms he left us.

These days people are inclined to go their own way, but as long as I am involved, I will continue to do the techniques and forms O-Sensei left us.

You mentioned before that students fail to move their hips sufficiently. Could you explain in more detail about the importance of the hips in practice?

The founder said that the key to effective hip work was in the legs, and the work of the brain depended on the arms. This means the hips cannot be stable unless the legs are steady. That is why I insist my students keep their back foot in line with the front foot when in hanmi. It is incorrect to move the back foot off that line. Although it may be okay to adopt a hanmi with the back foot close to the front leg, I think a hanmi where the legs are steady is best.

When you turn quickly to the rear keeping your front foot on the line, you should be able to recover your hanmi stance. But if your feet are not in line you will not be able to assume hanmi smoothly after turning 180 degrees without correcting the rear foot position. You will lose control and the motion will slow down. Recently I have placed great emphasis on hanmi even though perhaps it is not good to concentrate too much on this. Whenever I notice awkward movements in students I find that their legs are positioned wrongly.

If the limbs are moved in the wrong order, you no longer have an effective technique. If you cannot do correct footwork, you will not be able to use your hips effectively.

Do you teach ki no nagare techniques often at Iwama?

Yes, but only as part of a progression.

What do you mean by progression?

This refers to the order in which techniques are taught. At first we start with “hard” practice, then we teach ki no nagare, the study of moving with the movement of a partner. There are many kinds of ki no nagare, including slow and fast and free-style. I think everyone should learn these techniques but they must learn many other things first. This is why ki no nagare is called the last level.

If we practice ki no nagare techniques first what problems are we likely to encounter?

If you start by practicing ki no nagare, unless you are extremely skilful, your timing could be out and you would unable to do anything if your arms are held strongly. You can’t become strong or well trained that way. The founder used to say that if we wanted to be strong we should repeatedly practice techniques from grips. But these days in order to teach university students who study for only three or four years we mix ki no nagare practice with ordinary practice. It is a big mistake to think that there is no ki no nagare practiced at Iwama. The ki no nagare techniques of Iwama are executed faithfully as O-Sensei taught them.

O-Sensei’s style enables us to move smoothly even if we make a mistake in timing and are held firmly by an opponent; even if our movement is stopped for a moment, we can move without any problem with O-Sensei’s style.

Once aikido has its origins in swordsmanship and the taijutsu movements are based on the movements of the sword, is the study of ken and jo necessary in the practice of aikido?

The aikido that I learned consisted of both taijutsu and weapons techniques. We can use any type of weapon, but we mainly use the ken and jo. This is the only explanation I can give you. The founder explained aikido from many different viewpoints depending on the period and his state of mind. He said aikido was taijutsu that incorporated sword principles. So I believe aiki-ken and aiki-jo correspond to hanmi-ken and hanmi-jo. In other words, weapons techniques are expressed in the form of taijutsu, enabling you to enter into your opponent’s space and throw him.

The weapons-based techniques in taijutsu enable us to attack an opponent and throw him. I think taijutsu and weapons techniques should have a relationship, which is neither too close nor too remote. At the Iwama dojo I hold a weapons practice only once a week, so I am certainly putting the emphasis on taijutsu. But I think it is my duty, as one who was taught directly by the founder, to teach ken and jo to my students and to maintain the traditional teaching the founder left in Iwama.

As there are not many dojos where the ken is being taught, what should we do if we cannot find a dojo in our area where the ken and jo can be learned?

In Iwama we hire the municipal Budokan (martial arts hall) for weapons classes every Thursday when the Ibaragi dojo is closed. There is no weapons class for people who come to the evening classes at the Iwama dojo

How big is your new dojo?

It can only accommodate about 30 people. Mind you, I used to practice with O-Sensei alone, so the dojo was amply large enough for the two of us. On the other hand when some of the senior students of that time, such as Tadashi Abe, practiced with O-Sensei, we waited our turn and watched, and O-Sensei used to instruct us one-on-one. I can teach that way when necessary.

In fine weather we hold our Sunday training outdoors since there is plenty of space. When I teach at a dojo without much outdoor space, I adopt O-Sensei’s method and work with individual students one by one.

By the way, O-Sensei used to say that a limited number of sword movements have been part of jujutsu since ancient times. With these techniques you enter with your body in such a way that the opponent cannot avoid your movement. I am the only one who was taught this way by O-Sensei, so wherever I go many object to what I am teaching.

I can imagine your difficulty, under the circumstances, in sticking to what O-Sensei taught you.

Every year on the day before the Taisai [memorial service commemorating O-Sensei’s death] on April 29, Hombu students come from Tokyo to Iwama. In the past I used to teach them weapons, but after a while I stopped doing it. Then last year I reconsidered and felt I should teach weapons to them, so I held a small ken and jo class early in the morning. The Tokyo students got up early for this and enjoyed it, so I’ve decided to hold it this year as well. I plan to hold a taijutsu class with five or six of my students and five or six people from Tokyo on the evening of April 28 and the next day, if the weather is good, we will hold an outdoors training session in ken and jo.

A number of our readers are interested in learning more about the ken and jo. Are they taught at the dojo in Yoyogi Uehara, in Tokyo where your son teaches?

Yes, they are. Anyone who would like to learn these weapons should visit the Yoyogi dojo; I believe Wednesday is the day for ken and jo practice.

I am glad that you are still so active in Iwama and continuing to provide excellent weapons training. This will have a strong technical influence on aikido, which I believe will be good for the art. To change the subject a little, we have received a number of requests from our readers for information on Koichi Tohei Sensei, but we have not had the chance yet to speak with him. You must have met him shortly after World War II. Could you tell us anything you might remember from the days when Tohei Sensei was at the Iwama dojo?

I remember him quite well. Mr. Tohei started aikido during his school days, then he went off to war and came to the Iwama dojo after that. He seemed to us to be a very accomplished man, and he was our ideal, a wonderful man.

Ki no Kenkyukai (Shinshin Toitsu Aikido) practices include lectures about the workings of ki, and demonstrations of the unbendable arm and the unliftable body. Did you ever experience this kind of practice in Iwama after the war under O-Sensei?

No, I didn’t. It is a teaching method devised by Mr. Tohei after he studied different things, such as yoga under Tempu Nakamura [1876-1969] of Shinshin Toitsudo and misogi at the Ichikukai. Mr. Tohei is the one who made the greatest efforts in this area.

After he got married and started work he was too busy to come to Iwama so he converted a warehouse in the grounds of his home in Tochigi Prefecture into a dojo. I used to teach there when he was too busy. Then his business failed and he returned to aikido. After that he went to the United States where he would stay for a year, and then alternate by staying a year in Japan, and back to the U.S. the following year, and so on. I taught at Tochigi once a week during his absence.

I understand that Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei trained a great deal in Iwama. Who else among the Hombu dojo shihan trained here?

First of all, there was Tadashi Abe, then Koichi Tohei and Gozo Shioda, who stayed with his family for a while. All of them had been O-Sensei’s students before the war. Seigo Yamaguchi also stayed here for a while. Tetsutaka Sugawara spent three or four months, and Kazuo Chiba was here for two or three months after he injured his back. I think Sugawara and Chiba were here at the same time.

Before the war, the founder usually studied weapons by himself and did not teach these techniques to his students. It was during the Iwama period, mainly when only O-Sensei and I were left, that he began to teach weapons.

What do you think about the influence of Daito-ryu on aikido?

O-Sensei was greatly influenced by Daito-ryu. It is said that when he was practicing Daito-ryu he confronted many problems so he tried various other arts including Aioi-ryu before the war. After the war when he resumed practicing in Iwama his aikido had changed dramatically. Even though he had been influenced by Daito-ryu there are many distinct differences between O-Sensei’s aikido and Daito-ryu. For example, aikido is taught from hanmi, but hanmi is not taught in Daito-ryu. Neither is kokyuho. Although Daito-ryu has many tewaza (hand techniques), the body movements often clash with the opponent’s movement. Daito-ryu does not include the idea of the unity of the sword, jo and taijutsu. These are changes O-Sensei incorporated during the Iwama period. Many Daito-ryu techniques were not particularly effective against an opponent who had been trained even slightly in martial arts. Although there were a large number of techniques, many of them were not that effective.

Likewise, we sometimes hear that every aikido technique has ura and omote variations, but I think we should focus on what is most practical and effective. Certainly some techniques have clearly distinguishable ura and omote variations, but we should not worry too much about those that do not. The founder once said jokingly that there were no better techniques than koshinage (hip throws) and that he never got tired even if he practiced them from morning to night. Kokyunage and koshinage, which were once regarded as basic aikido techniques, are now being taught instead as applied or advanced techniques. I think it is unfortunate that this may have become necessary in order to preserve the techniques of aikido.

MORIHIRO SAITO PROFILE

Born in 1928 in Ibaragi Prefecture. Retired Japan National Railways employee. First taught by Morihei Ueshiba in Iwama in July 1946. Became Aikikai shihan in January 1959, and in 1969, after the death of the founder, became the chief instructor at the Ibaragi Dojo and guardian of the Aiki Shrine in Iwama. Author of the well-known five-volume work, Traditional Aikido, and the short manual Takemusu Aiki. Travels regularly to both the U.S. and Europe.